This post is the last in a series of posts extending the talk I gave at Glasgow University as part of the Handknitted Textiles & the Economies of Craft in Scotland workshop series.

I am fascinated by knitters' hands. No matter who we are - whether unsure beginners, lifestyle knitters, industry professionals, textile conservationists or artists - we all engage with the craft using our hands. We may hold the yarn in a myriad of ways and work the stitches at our own pace, but knitting is a tactile craft. The fabric is created by our hands. You can tell the difference between handknitted and machine-knitted fabric. Hand-knitted fabric holds the story of whoever made it. It has presence.

This post is the last in a series of posts extending the talk I gave at Glasgow University as part of the Handknitted Textiles & the Economies of Craft in Scotland workshop series.

I am fascinated by knitters' hands. No matter who we are - whether unsure beginners, lifestyle knitters, industry professionals, textile conservationists or artists - we all engage with the craft using our hands. We may hold the yarn in a myriad of ways and work the stitches at our own pace, but knitting is a tactile craft. The fabric is created by our hands. You can tell the difference between handknitted and machine-knitted fabric. Hand-knitted fabric holds the story of whoever made it. It has presence.

I think it is this echo of presence - the shadow of the knitter's hands - that is so alluring to textile artists.

Roxane Permar is one of the people behind the Mirrie Dancers project - a Shetland-based arts project combining traditional lace knitting with state-of-the-art technology. Shetland knitting heritage is a complex story but Permar decided to take what is often a dark story and literally shed light on it by projecting knitted lace sample onto the Mareel arts venue.

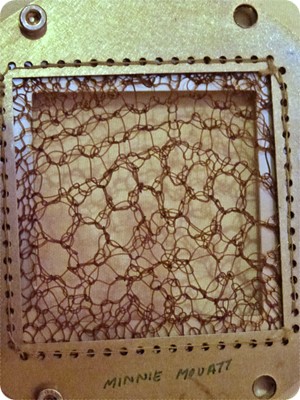

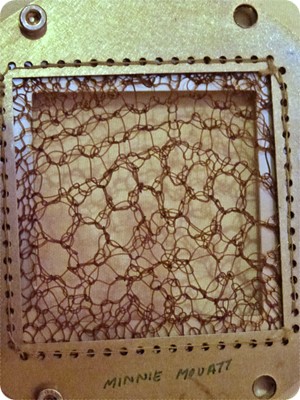

The Mirrie project involved a large team of highly skilled and dedicated Shetland lace knitters spread out across the islands who were all asked to knit a sample of lace in a heat-resistant material. The choice of material proved to be a surprising point of contention: some of the knitters refused to work in other material than fine Shetland wool. Other knitters embraced the task with surprising results - one of them started to play around in order to see how far you can take Shetland lace. Anne Euston is now pursuing a textiles degree specialising in a modern interpretation of lace knitting (you can see an example of her work on Kate Davies' blog).

I was intrigued by how far you can take lace knitting and what you can do with it. What does it look like when you project something that fine and minute up on a wall? I looked at the samples Roxane had brought with her - they were so delicate and obviously crafted with great skill and care - and yet when they were blown up, they became disembodied, abstract and strange. I no longer noticed the elegant stitches - I wondered about the holes, the gaps, and the absences caught and distorted by the light.

I thought Mirrie Dancers was incredibly successful - it made me think about the gaps and absences in how we approach about Shetland (lace) knitting today.

By for me, it always comes back to the twin ideas ofpresence and absence*.

The Material Culture students at Glasgow University learned how to knit as part of their Masters. They will go on to work in museums and as field archaeologists - and will be handling handcrafted artefacts as part of their everyday working life. Knitting, Dr Nyree Finlay argued, was a way of making them more keenly aware of both the workmanship behind the artefacts but also what it means that something is handmade.

Did they? Some of them never taught themselves to knit. One girl could cast on, but could not knit. Another could knit (but not cast on). I wondered if they had thought about the materials they used - but they had been so focused on learning the craft that they hadn't thought beyond a basic budget and colours. I don't know why but that slightly disappointed me - I get that mastering the craft was foremost in their minds, but I had hoped they would take the opportunity to also engage with the actual material circumstances of the craft.

And this is where I am left to write about how I engage with knitting as a cultural activity.

My "problem" as a designer is that I tend to start with very abstract concepts (such as Palaeolithic marine archaeology) and I have to spend a lot of time trying to parse that into a commercially viable pattern collection. The collection following Doggerland is rooted in something even more High Concept - and while my ideas are probably more suited to being explored by textile art (hat tip Deirdre Nelson!) I keep returning to my obsession with accessibility. I want to enable other people to knit my ideas and be able to wear them. I want to make meaning through knitting but simultaneously enable others to construct their own meanings and knit their own stories.

(A huge thank you to Professor Lynn Abrams and Dr Marina Moskowitz for inviting me to this series of workshops.)

* I blame myself for reading literary theory at an age when others were out partying. That sort of thing wreaks havoc.