Note from Karie: I’m currently very busy working on my forthcoming book, so over the next few weeks you will read a series of guest posts on creativity, making and identity penned by some very awesome people. You are in for a real treat as they explore our shared world of making. We are joined this week by Anna Fisk who is an academic based at the University of Glasgow. I know Anna from my knitting circles and always enjoy talking to her about the intersection of religion and culture. Anna’s craft practice is focused on the world around her and the changing seasons, from her Dear Green Shawl design available at p/hop to the natural dyeing, spinning and felting she blogs about at Knit Wild Studio. I asked Anna if she would write about her work researching knitting and making. I hope you'll enjoy this as much as I enjoy my conversations with Anna.

--

Back when I was working on my PhD thesis in feminist theology and literature, I realised that being a knitter was a much bigger part of my identity than any religious affiliation ever had been. My account of learning to knit was probably the most significant story I told about myself. The therapeutic nature of the process of knitting, and sense of achievement in the end products, enabled me to cope with depression and anxiety more than any ‘spiritual’ practices. It was making things that gave me a sense of meaning, and oriented how I approached the world.

Back when I was working on my PhD thesis in feminist theology and literature, I realised that being a knitter was a much bigger part of my identity than any religious affiliation ever had been. My account of learning to knit was probably the most significant story I told about myself. The therapeutic nature of the process of knitting, and sense of achievement in the end products, enabled me to cope with depression and anxiety more than any ‘spiritual’ practices. It was making things that gave me a sense of meaning, and oriented how I approached the world.

Being part of the knitting community, I knew my experience of craft as transformative and sustaining was far from unusual. So after finishing my doctorate I wanted to engage with research with other people about the significance of knitting in their lives, and see if I was right in my hunch this was related to religion in some way.

This meant thinking about the very definition of ‘religion’. I got interested in contemporary scholarship on ‘lived’ religion, which is about everyday practices, material things, and the stories that give us meaning and help us to cope, rather than a set of beliefs about higher powers or abstract doctrines. I also read up on the secularization debates, which ask whether religion is disappearing altogether or instead morphing into new forms. These range from holistic mind-body-spirit practices to environmental activism; or the civil religion of nationalism, family values, capitalism, and human rights discourse.

I started researching other people’s knitting practice, firstly through participant observation of two knitting groups in Glasgow. I noticed the groups (as well as yarn festivals, Ravelry, podcasts…) worked in a similar way to religious institutions. People who’d just moved to the city would join a knitting group to make friends; attending regularly provided routine and support, and helped people feel less isolated. We knitters also have a shared identity and language (‘stash’, ‘squishing’ yarn, etc.). So the first theme of my research is how knitting as a subculture, providing belonging and identity, can work as an implicit religion.

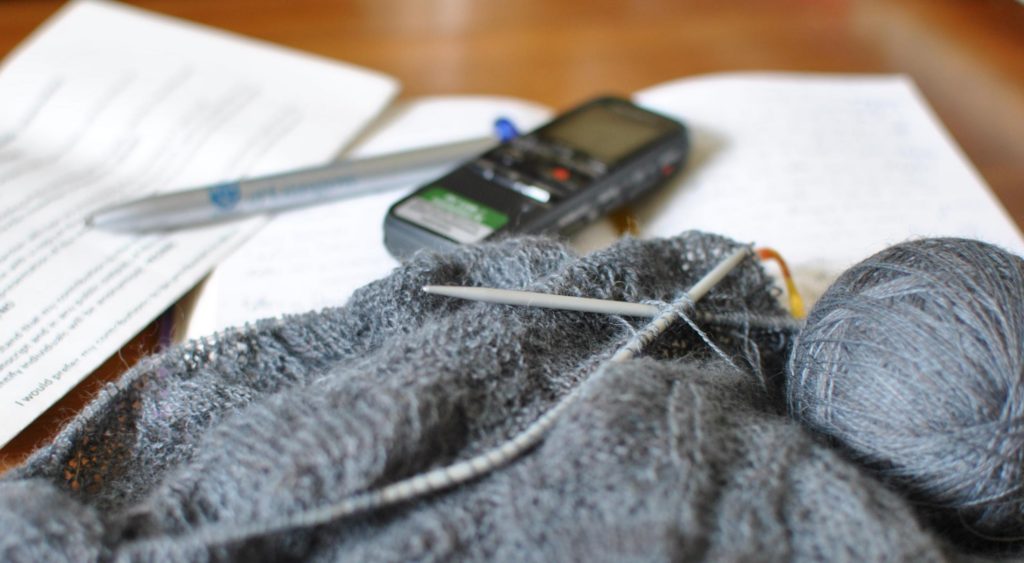

The second major theme came out more in a focus group session and individual interviews with knitters across central Scotland. These were recorded on my trusty dictaphone, leaving my hands free for knitting while I talked to the participants, who were also knitting.

Through these conversations it became clearer to me that the effects of knitting on wellbeing have parallels with holistic spiritual practices such as yoga or mindfulness meditation. Many of my participants described knitting as ‘therapeutic’ and a way of getting through difficult times and situations. Some had deliberately started knitting because of these benefits.

The theme I’m most interested is what I call sacred connections. As a knitter, I mark really important life events and relationships by knitting them. As do many other knitters, from graduation shawls, booties for grandchildren, to braving that sweater curse for your significant other. This includes the craftivism of yarnbombing and pussy hats; charity knitting after major disasters (when you know that just sending money would probably be more effective, but in knitting penguin sweaters or blankets for the homeless you’re really doing something). This is one aspect of how we use knitting as way of connecting with—ritualising and materialising—the things that are most important (or ‘sacred’) to us.

The other aspect relates to this urge I have, whenever I find something that I love or am fascinated by, to render it in wool, to knit it. I see this throughout our knitting world, including in the work of designers like Karie, whose patterns are inspired by Glasgow tenement tiles and best-loved artists and novelists; who creates whole pattern collections based on her historical specialisms, not just as an intellectual exercise but also about connecting with landscape, heritage, and materiality.

Beyond what this tells us about knitters (who are interesting enough!), I also think it tells us something about the kinds of things that are most important—sacred—for people in the (post)secular, late-modern world: love and family, cultural tradition, political commitments, the natural and built environment, our bodies.

I’m interested in how conversations around knitting—and craft more generally—are part of the cultural trend (beginning with Romanticism) of attempting to reconnect with what we feel we’ve lost in modern life, from a sense of place, to taking it slow, to being truly part of the material world around us. Making things with our own hands, paying attention to the whole process, out of materials we know the provenance of, gives a profound satisfaction and sense of connection that for many of us is indeed sacred.

(I knitted the Biophilia shawl (which is about 'hypothetically innate human tendency to feel an emotional attachment to the natural world') while I was conducting the interviews.)

I have a couple of articles from this research coming out soon, but I want to write a whole book on the topic eventually. So the work is very much ongoing. If you’d like to share your stories with me, I would love to hear from potential participants, particularly on the sacred connections theme. Even if you’d just like to hear more about this research, do please get in touch!